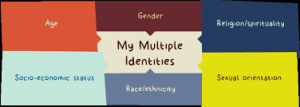

Ecofeminism, as we’ve learned, can mean may different things, and have many aspects of feminism associated with it. This topic, in and of itself, studies the relationship between women and nature, as well as the oppressions that come along with them, and how they relate to each other. As well, each individual person has their own set of identities that overlap and interconnect with each other. Because part of understanding ecofeminism is understanding women and their oppression, we must look more into being a woman, which has many different aspects. Because of this, the term intersectionality was born.

In their reading, Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism, A.E. Kings refers to this term as a “web of entanglement”, as opposed to a simple crossing of paths (Kings, 2017). It describes a varied list of categories that make a person who they are – “gender, sexuality, race, or class; while encircling spirals depict individual identities” (Kings, 2017). Think of these spirals and crossing paths as you would a spider’s web: there are many major categories ‘stuck’ together by “two or more intersecting or conflicting social categories” (Kings, 2017). While our gender might have us facing one type of oppression, our race or sexuality may have us facing another; or even the opposite. I thought this was such a beautiful example of how intersectionality works – these aren’t just stand-alone, tentpole characteristics. They are all a part of us and work together to create the complex beings that we are.

The term intersectionality is largely credited to Kimberlé Crenshaw, who is a critical legal race scholar, and coined the term in 1989 (gov.scot, 2022). She wanted to “represent and capture the specificity of the discrimination faced by black women” (Kings, 2017). Not only are black women oppressed by their gender, they are also oppressed for their race. This type of issue isn’t quite covered under ecofeminism, as it more uses the blanket term of ‘all women’. Leah Thomas’ article The Difference Between Ecofeminism & Intersectional Environmentalism explores this perspective in more detail, and really exemplifies the core of what intersectionality means. We have read works from multiple types of people in this course, but women of color deal with more oppression that just that of their gender. She reminds readers that the color of her skin is not “an extra “add on” to my feminism or environmentalism” (Thomas, 2020), but feels that intersectionality is more inclusionary to her lived experience as a woman.

There is another aspect to all this, though, as the topic of intersectionality is not only how we see ourselves, but how we see other people and our relationships to them. In Beverly Tatum’s The Complexity of Identity, she states that “social scientist Charles Cooley pointed out long ago, other people are the mirror in which we see ourselves” (Tatum, 1). She calls this the ‘looking glass self’ which, to go deeper into the conjoined web of intersectionality, explains how we are not just a list of checkboxes, affected by different aspects of ourselves at any given time. We are social beings, and are made up of what we learn from our families, our communities and the world around us. “Erik Erikson, the psychoanalytic theorist who coined the term identity crisis, introduced the notion that the social, cultural, and historical context is the ground in which individual identity is embedded” (Tatum, 1). I have long thought this way, myself. I have always learned equally from people I’ve known for a short while or a lifetime, about the kind of person I want to be, and what I want to experience.

Tension can come into play, though, when it comes to the differences between what she calls the ‘dominant’ and ‘subordinate’ groups. Tatum references Jean Baker Miller who “points out that dominant groups generally do not like to be reminded of the existence of inequality” (Tatum, 4). Furthermore, “they can even believe both they and the subordinate group share the same interests and, to some extent, a common experience” (Tatum, 4). I loved this quote from Tatum’s reading because it so clearly showed how the imbalances work, and how interdependent they are on the other. The subordinates need to learn about and study the dominant people in their world, but dominants “can avoid awareness because… it is easy to believe everything is as it should be” (Tatum, 4).

But this is dangerous territory, to not explore the world around us, and just assume everything is working out as it should. It is both within and outside of our respective groups that we will find people working for and against us. “Traditional feminist theory,” Dorothy Allison states, in A Question of Class, “has had a limited understanding of class differences and…implies that we are all sisters who should only turn our anger and suspicion on the world outside” (Allison). In this quote, I find some relevance to my own life when she comments on being angry at people outside the LGBTQIA+ community – the key word here is ‘implies’. We often look outward towards our oppressors to express our frustrations – why are they acting this way, and doing this to us? But in some cases, it could very well be the people in our own ‘groups’ that are perpetuating certain oppressions.

When it comes to the way women are treated, I have realized that certain learned behaviors may be driving the way women treat other women, which works directly against our own interests. As a cis, white, heterosexual woman, I will never fully understand the feelings behind what Allison writes here. Yes, I have had certain advantages, but one “strike” against me is that I am woman, so I am faced with certain expectations and judgements. So, all I can do is try to relate and understand through things that I have experienced. She mentions how “the idea of writing stories seemed frivolous when there was so much work to be done,” but this is the way it should be (Allison). As she mentions, we are so harsh on ourselves, because of the way that society is contrived. Speaking out, even in the form of writing, will help break down these stigmas and get us to treat ourselves with more grace.

“Claiming your identity in the cauldron of hatred and resistance to hatred is infinitely complicated, and worse, almost unexplainable.”

~Dorothy Allison, A Question of Class

Outside works cited:

The Scottish Government. “Using Intersectionality to Understand Structural Inequality in Scotland: Evidence Synthesis.” Scottish Government, The Scottish Government, 10 Mar. 2023, https://www.gov.scot/publications/using-intersectionality-understand-structural-inequality-scotland-evidence-synthesis/pages/3/.