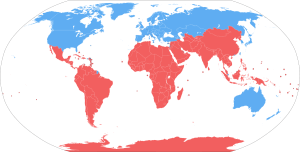

The term “Global South” may sound like it’s referring to a specific part of the world, but in actuality it is more of a metaphor for lower-income and lesser-developed countries. Asian, African and South American countries fall into this category, and are affected by what is called environmental degradation, on a more serious level than other countries. Environmental degradation is an issue that affects many people around the world, yet it’s one that women are found to be uniquely affected by. It entails anything from the disturbance or “destruction of ecosystems and the extinction of wildlife” to the deterioration of environmental “resources such as air, water and soil” (unescwa.org).

Source: Wikipedia

When the sanitation, access and safety of our world’s resources fail, women suffer. I was intrigued by the UN Water article we read, which described the issues women and girls are facing; many of which likely wouldn’t occur to most people residing in the ‘Global North’. Their safety is put at risk, simply by having to share restroom facilities with men and boys, and aren’t involved in decisions made around sanitation services, and thus are assured “their continued marginalization” (unwater.org). Aside from issues surrounding safety and cleanliness, women’s hygiene and pregnancy needs are not being adequately met.

The piece that really stuck with me after reading this, was the fact that women and girls are typically the ones that fetch water for their families. I wanted to learn more about this, so I referred to a Unicef article, which explained this process, which they referred to as a “colossal waste of time” for these women (unicef.org, 2016). “In sub-Saharan Africa,” they explain, “one roundtrip to collect water is 33 minutes on average in rural areas and 25 minutes in urban areas”, numbers that vary depending on location. Men are only reported to contribute a fraction of this time to fetching, with time spent being reported as being from 6-10 minutes. This time spent takes away any time women and children could be in school or working to support their families. This issue alone well advocates for the need of having running water in all homes, in order to make things generally safer for women.

Source: freepik.com

The readings of Agarwal and Hobgood-Oster both delve into this dire issue in their works, but bring up different points. One of the main similarities the authors discuss is that femininity is deeply connected to nature and the Earth. Agarwal mentions many different scholars and their opinions on ecofeminism, all of which are of varying degrees of how tightly tied to nature women are. But, she says, “they accept the view that women are ideologically constructed as closer to nature because of their biology” than men are (Agarwal, 121). What Hobgood-Oster didn’t really mention in her essay was this breakdown of how non-white women are affected by the lack of diversity in nature. While she recognized that more women of color need to be in positions of authority when it comes to environmental issues, I felt that her reading focused more on the oppressive relationships between what she referred to as ‘dualistic hierarchies’. One point she does make in regards to criticism of ecofeminism is that many people don’t ascribe to this movement as they feel it doesn’t represent all the different nuances that feminism contains.

I’m more apt to lean towards Agarwal’s view on ecofeminism, as it takes into account that feminism, women, and nature aren’t necessarily painted in such broad strokes. Hobgood-Oster’s work realizes that racism plays a part in the discussion around ecofeminism, but Agarwal goes a little deeper. In her essay The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India, she references work by Carolyn Merchant. She states that in regard to her stance on ecofeminism, it “fails to differentiate among women by class, race, ethnicity” and other characteristics, which she feels leaves out other important forms of oppression that aren’t specifically about gender.

Works Cited:

Agarwal, Bina. “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India.” Feminist Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1992, pp. 119–58. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3178217. Accessed 13 Feb. 2023.

“Collecting Water Is Often a Colossal Waste of Time for Women and Girls.” UNICEF, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-collecting-water-often-colossal-waste-time-women-and-girls.

“Environmental Degradation.” United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 31 Dec. 2015, https://archive.unescwa.org/environmental-degradation.

“Water and Gender: UN-Water.” UN, https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-and-gender.

Amanda, your chosen imagery for this week was really impactful, the color coded picture of the globe jumped out immediately. Prior to this week I knew what the terms Global South and North were. However seeing them in real borders solidified something for me. Before seeing that image I did not think the Global South included that much of Asia but in my mind I do not know why I assumed that parts of Europe like the Ukraine were. Maybe because of the war and conflict happening in parts of Europe.

What I really appreciated about the non- Western readings this week was the emphasis on ecological impacts from the systems of oppressions like colonization, patriarchy, and racism. One thing I also started to think about this week is time, your blog raised an important note around time. Women spend a significant time during their days taking care of their ecosystems and performing labor intense acts. Like the UN recognizes water is a human right, I second that access to clean safe drinking water for women living in the Global South takes a significantly longer time to obtain. This is typically different for women living in the Global North that more than likely have more access to safe water then their counterparts in the Global South.

The facts you chose to highlight about women in the Global South going through labor disparities, among other things, drove a point home about the duality of ecofeminism and environmentalism. The ways in which women are treated in relation to men and the environment are the basis for ideas like ecofeminism. To your point, if we started focusing on how to improve the disparities in women’s and girls’ lives we could be well on our way to making communities safer for all.